Society for the Preservation of Traditional Kanazawa Gold Leaf

Background

There are two grades of gold leaf produced and sold in Kanazawa. The first, called entsuke gold leaf, has a history of over four hundred years and is made using traditional techniques and materials. The second, called tachikiri gold leaf, uses modern processes and materials such as carbon-coated glassine paper. While traditional gold leaf is more labor-intensive, it is almost exclusively preferred over modern gold leaf for the restoration of National Treasures and Important Cultural Properties.

Although the two have numerous differences, a distinguishing feature of traditional gold leaf is the use of handmade washi paper in the goldbeating process. This specially prepared paper has a crucial impact on the quality of the finished gold leaf, and more time and effort are spent on the preparation of the paper than on any other step in the process.

Today, shifting lifestyles and an economy based on mass production for mass consumption have led to the decline of many traditional practices. Gold leaf production is decreasing, and veteran goldbeaters struggle to find successors to carry on the craft.

Mission

Producing a single sheet of entsuke gold leaf requires years of experience and specialized tools. However, the knowledge and skills passed down for generations are now in danger of disappearing, and this vital piece of traditional culture may be lost. Training new practitioners to preserve these techniques and skills for future generations is of utmost importance.

To this end, we have founded this society to help preserve the skills and knowledge required to produce entsuke gold leaf and unite the practitioners of our craft to overcome these challenges together.

Traditional Gold Leaf as Decoration

Entsuke gold leaf is used as a decorative material in architecture, fine arts, and crafts. It is essential for the restoration of National Treasures and Important Cultural Properties.

Nikkō Tōshōgū Shrine

Honganji Kanazawa Betsuin Temple

Kanazawa Gold Leaf

Gold leaf is gold that has been hammered into incredibly thin sheets only 1/10,000 of a millimeter thick. Almost all of Japan’s gold leaf is produced in the city of Kanazawa.

Gold leaf is made by stacking thin ribbons of gold between sheets of goldbeating paper to create a packet. A goldbeater then uses a mechanized hammer to methodically beat the packet, causing the gold to flatten and expand into thinner and thinner sheets over repeated stages of hammering.

There are two grades of gold leaf produced and sold in Kanazawa: traditionally made gold leaf, called entsuke gold leaf, and modern gold leaf, called tachikiri gold leaf, which uses modern techniques and sulfuric acid paper.

Entsuke Gold Leaf

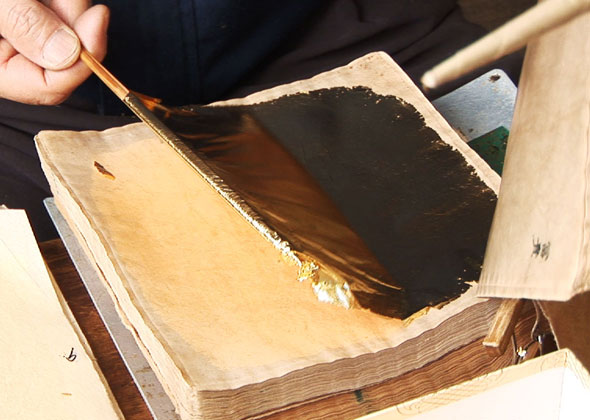

Entsuke (lit. “bordered” or “framed”) gold leaf has a history of over four hundred years. The name refers to how the finished leaf is sold on a sheet of paper large enough to create a border around the gold. While many of the world’s goldbeating traditions use animal membranes or mylar, entsuke gold leaf is beaten between sheets of washi paper. This special goldbeating paper (uchigami) is made from the fibers of the ganpi shrub and treated with naturally produced straw lye and persimmon tannins. The finished leaf is carefully checked one sheet at a time and cut to a standard size and shape using a bamboo tool.

Tachikiri Gold Leaf

Tachikiri (lit. “cut”) gold leaf was developed in the late 1960s. In place of the traditional washi goldbeating paper, tachikiri gold leaf uses industrially produced glassine paper for the goldbeating process. The finished packet of gold leaf is cut into a square—paper and all—removing the edges and giving the leaf its name.

The use of washi paper in the goldbeating process is a defining characteristic of traditional gold leaf. Even more than the goldbeating technique itself, the leaf depends on the innate qualities of the goldbeating paper (uchigami), which determines how the incredibly thin gold flattens and expands. The ganpi paper used for goldbeating is a unique variety of washi containing fine minerals. The paper requires fine attention to detail and a high level of mastery to produce, and its importance in the goldbeating process does not allow for shortcuts or substitutes. The knowledge surrounding its production forms the marrow of traditional Japanese goldbeating. Close to 90% of the labor required to produce entsuke gold leaf is devoted to preparing and maintaining the goldbeating paper. The paper is indispensable in the production of quality gold leaf.

Characteristics of Entsuke Gold Leaf

Gold is a precious metal, and its value is recognized throughout the world. Gold leaf was developed as a more economical way of using gold for decorations, utilizing the metal’s innate malleability to produce extremely thin sheets capable of covering larger areas with less gold.

An important characteristic of entsuke gold leaf is that the quality of the gold remains unchanged in the finished leaf. Traditional goldbeaters tirelessly refine their craft, working to produce thin, evenly stretched sheets of the highest quality.

Among specialists, entsuke gold leaf is praised for its soft appearance, luster, and edge quality—although for most people, distinguishing between entsuke and tachikiri gold leaf based on appearance alone is difficult.

Finally, entsuke gold leaf is made entirely with natural materials. As a result, entsuke—rather than tachikiri—is used for edible gold leaf products.

Entsuke Gold Leaf Designation Requirements

Entsuke gold leaf must be produced using traditional methods and tools.

- 1.The final gold leaf (haku) must be beaten using haku uchigami goldbeating paper consisting of traditionally made ganpi paper with minerals (doroiri ganpishi). This may include najioshi, futamatashi, nakajimashi, or another type of washi of a comparable make.

- 2.The early-stage gold sheet (zumi) must be beaten using traditionally made washi paper consisting of rice straw and kōzo mulberry fibers.

- 3.The haku uchigami goldbeating paper must be treated with lye obtained by burning rice straw.

- 4.The final goldbeating (haku uchi) must follow the process of bundling (hikiire), molding (uchimae), rebundling (watashi shigoto), molding (uchimae), grading (nuki shigoto), and trimming/booking (utsushi shigoto).

- 5.The final step in the goldbeating process (haku utsushi) must be conducted on a leather board (kawaban); each sheet of gold leaf must be individually trimmed using a bamboo wagon (takewaku) and interleaved with hakuaishi made from mitsumata paper.

- 6.The hakuaishi used for interleaving must be mitsumata paper from Tsuyama, Okayama prefecture.

History of Gold Leaf in Japan

Early examples of gold leaf in Japan include the seventh-century statues of the Shitennō (Four Heavenly Kings) at Horyuji temple, and the murals in the Takamatsuzuka burial mound. An iconic example from the late Heian period (794–1185) is the Konjikidō at Chūsonji temple in Hiraizumi. The Konjikidō (“Golden Hall”), completed in 1124, is said to be the model for the legend of “Zipangu, the Land of Gold,” as told by the thirteenth-century Venetian explorer Marco Polo in The Travels of Marco Polo.

Following the Heian period, the art of gold leaf and gilding flourished—first with the advent of Kitayama culture under shogun Ashikaga Yoshimitsu (1358–1408), and later with the rise of Momoyama culture under the powerful warlord Toyotomi Hideyoshi (1537–1598). Kinkakuji temple, famously known as the Golden Pavilion, represents the pinnacle of Kitayama culture and is one of the most iconic examples of Japanese gilding.

Looking to the Edo period (1603–1867), the Nikkō Tōshōgū shrine is another renowned example of gilded architecture. The impressive Yōmeimon (“Sun Bright Gate”), which was recently restored, is gilded with 200,000 sheets of gold leaf.

Types of Kanazawa Gold Leaf

Today, gold leaf is predominantly produced in five shades.

The shade with the highest gold content is called gomōshoku and consists of 98.0875% gold. The shade with the lowest content is No. 4 leaf and contains 94.438% gold. Higher gold content results in a reddish hue, while lower gold content has a stronger yellow hue.

The temples of Kyoto predominantly use No. 1 leaf, which has a gold content of 97.666%. The Nikkō Tōshōgū shrine uses No. 3 leaf, with a gold content of 95.795%.

Different appearances can be achieved depending on how the leaf is applied. While it is common to affix the gold leaf to urushi lacquer, animal glue is also used for gold screens and other objects. Lacquer can be burnished or finished in a variety of ways to affect the appearance of the applied leaf. For example, in some parts of Japan, Buddhist altars are gilded using a technique called omo oshi; the gold leaf is applied over a relatively thick coat of lacquer to produce a subdued, matte finish. In other regions, the lacquer is almost entirely removed to produce a mirror finish when gilded.

Japanese gold leaf can be applied in a wide variety of ways depending on the tastes of the region or the individual applying it.

- Type

- Percentage

- Gomōshoku

- 98.0871.9420.971

- No. 1

- 97.6661.3580.976

- No. 2

- 96.7212.4080.87

- No. 3

- 95.7953.3430.862

- No. 4

- 94.4384.9010.661

How Traditional Gold Leaf is Made

Gold leaf is made by stacking thin ribbons of gold between sheets of handmade washi paper to create a thick packet. A goldbeater then uses a mechanized hammer to methodically beat the packet, causing the gold to flatten and expand. The expanded gold is divided, and the process is repeated until the sheets of gold are just 1/10,000 of a millimeter thick.

The process for making traditional Japanese gold leaf consists of three parts:

- Initial Goldbeating

Zumi - Final Goldbeating

Haku - Paper Preparation

Kamijikomi

For the initial goldbeating stage, goldbeaters known as zumiya cast gold ingots to be made into gold leaf. The ingots are then rolled into a thin ribbon and beaten to a thickness of 1/1,000 of a millimeter. The resulting thick leaf is called zumi. This is then given to goldbeaters known as hakuya for the final goldbeating stage to produce the finished gold leaf (haku), which has a thickness of only 1/10,000 of a millimeter.

Goldbeating paper is essential for each step of the process. Both zumiya and hakuya purchase paper from traditional papermakers, which they then treat and mature in a process called kamijikomi.

History of Gold Leaf in Kanazawa

- 1593

- Maeda Toshiie (1538–1599) orders the production of gold and silver leaf during his deployment to Korea. (Gilded roof tiles have been unearthed at the ruins of Kanazawa Castle Imori Moat and other excavation sites)

- 1667

- The shogunate strictly regulates gold leaf, making it illegal to produce.

- 1696

- Domestic production and sale of gold and silver leaf are restricted to the metal leaf guild Hakuza, established in Edo (present-day Tokyo).

- 1808

- Kanazawa Castle burns down. Hakuya Isuke invites goldbeaters from Kyoto and produces 16,000 sheets of 12 cm2 gold leaf for the reconstruction effort.

- 1819

- Yasudaya Sukesaburo of Zaimokucho and his apprentices produce leaf for the Takezawa Palace.

- 1864

- Kanazawa establishes its reputation for gold leaf.

- 1868–1912

- Demand for gold leaf increases beginning in 1872–3.

Gold leaf production ceases in Tokyo. Superior technique and local water quality, which allowed for better goldbeating paper, paved the way for Kanazawa’s monopoly on metal leaf. - 1915

- Miura Hikotarō (1869–1939) completes his mechanized goldbeating hammer.